Chapter XXXII - The Martin Book

Electric Discharge in Vacuum Tubes

In The Electrical Engineer of June 10 I have noted the description of some experiments of Prof. J. J. Thomson, on the "Electric Discharge in Vacuum Tubes," and in your issue of June 24 Prof. Elihu Thomson describes an experiment of the same kind. The fundamental idea in these experiments is to set up an electromotive force in a vacuum tube—-preferably devoid of any electrodes—by means of electro-magnetic induction, and to excite the tube in this manner.

As I view the subject I should, think that to any experimenter who had carefully studied the problem confronting us and who attempted to find a solution of it, this idea must present itself as naturally as, for instance, the idea of replacing the tinfoil coatings of a Leyden jar by rarefied gas and exciting luminosity in the condenser thus obtained by repeatedly charging and discharging it. The idea being obvious, whatever merit there is in this line of investigation must depend upon the completeness of the study of the subject and the correctness of the observations. The following lines are not penned with any desire on my part to put myself on record as one who has performed similar experiments, but with a desire to assist other experimenters by pointing out certain peculiarities of the phenomena observed, which, to all appearances, have not been noted by Prof. J. J. Thomson, who, however, seems to have gone about systematically in his investigations, and who has been the first to make his results known. These peculiarities noted by me would seem to be at variance with the views of Prof. J. J. Thomson, and present the phenomena in a different light.

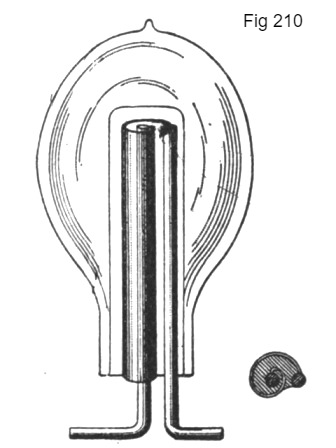

My investigations in this line occupied me principally during the winter and spring of the past year. During this time many different experiments were performed, and in my exchanges of ideas on this subject with Mr. Alfred S. Brown, of the Western Union Telegraph Company, various different dispositions were suggested which were carried out by me in practice. Fig. 210 may serve as an example of one of the many forms of apparatus used. This consisted of a large glass tube sealed at one end and projecting into an ordinary incandescent lamp bulb. The primary, usually consisting of a few turns of thick, well-insulated copper sheet was inserted within the tube, the inside space of the bulb furnishing the secondary. This form of apparatus was arrived at after some experimenting, and was used principally with the view of enabling me to place a polished reflecting surface on the inside of the tube, and for this purpose the last turn of the primary was covered with a thin silver sheet. In all forms of apparatus used there was no special difficulty in exciting a luminous circle or cylinder in proximity to the primary.

As to the number of turns, I cannot quite understand why Prof. J. J. Thomson should think that a few turns were "quite sufficient," but lest I should impute to him an opinion he may not have, I will add that I have gained this impression from the reading of the published abstracts of his lecture. Clearly, the number of turns which gives the best result in any case, is dependent on the dimensions of the apparatus, and, were it not for various considerations, one turn would always give the best result.

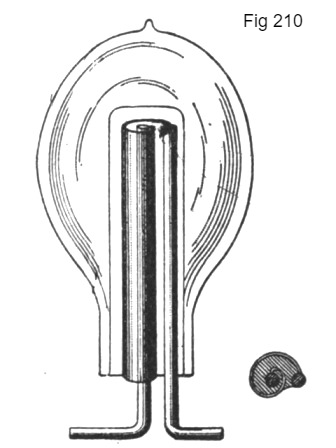

I have found that it is preferable to use in these experiments an alternate current machine giving a moderate number of alternations per second to excite the induction coil for charging the Leyden jar which discharges through the primary—shown diagrammatically in Fig. 211,—as in such case, before the disruptive discharge takes place, the tube or bulb is slightly excited and the formation of the luminous circle is decidedly facilitated. But I have also used a Wimshurst machine in some experiments.

Prof. J. J. Thomson's view of the phenomena under consideration seems to be that they are wholly due to electro-magnetic action. I was, at one time, of the same opinion, but upon carefully investigating the subject I was led to the conviction that they are more of an electrostatic nature. It must be remembered that in these experiments we have to deal with primary currents of an enormous frequency or rate of change and of high potential, and that the secondary conductor consists of a rarefied gas, and that under such conditions electrostatic effects must play an important part.

In support of my view I will describe a few experiments made by me. To excite luminosity in the tube it is not absolutely necessary that the conductor should be closed. For instance, if an ordinary exhausted tube (preferably of large diameter) be surrounded by a spiral of thick copper wire serving as the primary, a feebly luminous spiral may be induced in the tube, roughly shown in Fig. 212. In one of these experiments a curious phenomenon was observed; namely, two intensely luminous circles, each of them close to a turn of the primary spiral, were formed inside of the tube, and I attributed this phenomenon to the existence of nodes on the primary. The circles were connected by a faint luminous spiral parallel to the primary and in close proximity to it. To produce this effect I have found it necessary to strain the jar to the utmost. The turns of the spiral tend to close and form circles, but this, of course, would be expected, and does not necessarily indicate an electro-magnetic effect; Whereas the fact that a glow can be produced along the primary in the form of an open spiral argues for an electrostatic effect.

In using Dr. Lodge's recoil circuit, the electrostatic action is likewise apparent. The arrangement is illustrated in Fig. 213. In his experiment two hollow exhausted tubes H H were slipped over the wires of the recoil circuit and upon discharging the jar in the usual manner luminosity was excited in the tubes.

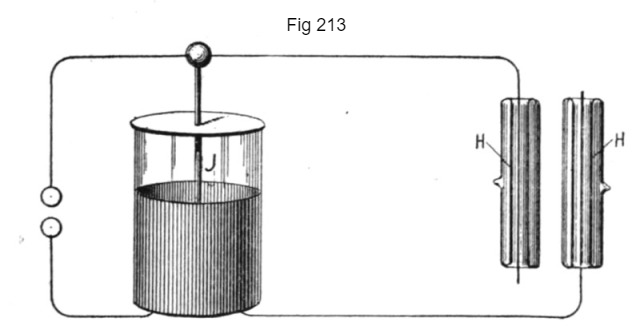

Another experiment performed is illustrated in Fig. 214. In this case an ordinary lamp-bulb was surrounded by one or two turns of thick copper wire P and the luminous circle L excited in the bulb by discharging the jar through the primary. The lamp-bulb was provided with a tinfoil coating on the side opposite to the primary and each time the tinfoil coating was connected to the ground or to a large object the luminosity of the circle was considerably increased. This was evidently due to electrostatic action.

In other experiments I have noted that when the primary touches the glass the luminous circle is easier produced and is more sharply defined; but I have not noted that, generally speaking, the circles induced were very sharply defined, as Prof. J. J. Thomson has observed; on the contrary, in my experiments they were broad and often the whole of the bulb or tube was illuminated; and in one case I have observed an intensely purplish glow, to which Prof. J. J. Thomson refers. But the circles were always in close proximity to the primary and were considerably easier produced when the latter was very close to the glass, much more so than would be expected assuming the action to be electromagnetic and considering the distance; and these facts speak for an electrostatic effect.

Furthermore I have observed that there is a molecular bombardment in the plane of the luminous circle at right angles to the glass—supposing the circle to be in the plane of the primary—this bombardment being evident from the rapid heating of the glass near the primary. Were the bombardment not at right angles to the glass the heating could not be so rapid. If there is a circumferential movement of the molecules constituting the luminous circle, I have thought that it might be rendered manifest by placing within the tube or bulb, radially to the circle, a thin plate of mica coated with some phosphorescent material and another such plate tangentially to the circle. If the molecules would move circumferentially, the former plate would be rendered more intensely phosphorescent. For want of time I have, however, not been able to perform the experiment.

Another observation made by me was that when the specific inductive capacity of the medium between the primary and secondary is increased, the inductive effect is augmented. This is roughly illustrated in Fig. 215. In this case luminosity was excited in an exhausted tube or bulb B and a glass tube T slipped between the primary and the bulb, when the effect pointed out was noted. Were the action wholly electromagnetic no change could possibly have been observed.

I have likewise noted that when a bulb is surrounded by a wire closed upon itself and in the plane of the primary, the formation of the luminous circle within the bulb is not prevented. But if instead of the wire a broad strip of tinfoil is glued upon the bulb, the formation of the luminous band was prevented, because then the action was distributed over a greater surface. The effect of the closed tinfoil was no doubt of an electrostatic nature, for it presented a much greater resistance than the closed wire and produced therefore a much smaller electromagnetic effect.

Some of the experiments of Prof. J. J. Thomson also would seem to show some electrostatic action. For instance, in the experiment with the bulb enclosed in a bell jar, I should think that when the latter is exhausted so far that the gas enclosed reaches the maximum conductivity, the formation of the circle in the bulb and jar is prevented because of the space surrounding the primary being highly conducting; when the jar is further exhausted, the conductivity of the space around the primary diminishes and the circles appear necessarily first in the bell jar, as the rarefied gas is nearer to the primary. But were the inductive effect very powerful, they would probably appear in the bulb also. If, however, the bell jar were exhausted to the highest degree they would very likely show themselves in the bulb only, that is, supposing the vacuous space to be non-conducting. On the assumption that in these phenomena electrostatic actions are concerned we find it easily explicable why the introduction of mercury or the heating of the bulb prevents the formation of the luminous band or shortens the after-glow; and also why in some cases a platinum wire may prevent the excitation of the tube. Nevertheless some of the experiments of Prof. J. J. Thomson would seem to indicate an electromagnetic effect. I may add that in one of my experiments in which a vacuum was produced by the Torricellian method, I was unable to produce the luminous band, but this may have been due to the weak exciting current employed.

My principal argument is the following: I have experimentally proved that if the same discharge which is barely sufficient to excite a luminous band in the bulb when passed through the primary circuit be so directed as to exalt the electrostatic inductive effect—namely, by converting upwards—an exhausted tube, devoid of electrodes, may be excited at a distance of several feet.

SOME EXPERIMENTS ON THE ELECTRIC DISCHARGE IN VACUUM TUBES

BY PROF. J. J. THOMSON, M.A., F.R.S.

The phenomena of vacuum discharges were, Prof. Thomson said, greatly simplified when their path was wholly gaseous, the complication of the dark space surrounding the negative electrode, and the stratifications so commonly observed in ordinary vacuum tubes, being absent. To produce discharges in tubes devoid of electrodes was, however, not easy to accomplish, for the only available means of producing an electromotive force in the discharge circuit was by electro-magnetic induction. Ordinary methods of producing variable induction were valueless, and recourse was had to the oscillatory discharge of a Leyden jar, which combines the two essentials of a current whose maximum value is enormous, and whose rapidity of alternation is immensely great. The discharge circuits, which may take the shape of bulbs, or of tubes bent in the form of coils, were placed in close proximity to glass tubes filled with mercury, which formed the path of the oscillatory discharge. The parts thus corresponded to the windings of an induction coil, the vacuum tubes being the secondary, and the tubes filled with mercury the primary. In such an apparatus the Leyden jar need not be large, and neither primary nor secondary need have many turns, for this would increase the self-induction of the former, and lengthen the discharge path in the latter. Increasing the self-induction of the primary reduces the E. M. F. induced in the secondary, whilst lengthening the secondary does not increase the E. M. F. per unit length. The two or three turns, as shown in Fig. 216, in each, were found to be quite sufficient, and, on discharging the Leyden jar between two highly polished knobs in the primary circuit, a plain uniform band of light was seen to pass round the secondary. An exhausted bulb, Fig. 217, containing traces of oxygen was placed within a primary spiral of three turns, and, on passing the jar discharge, a circle of light was seen within the bulb in close proximity to the primary circuit, accompanied by a purplish glow, which lasted for a second or more. On heating the bulb, the duration of the glow was greatly diminished, and it could be instantly extinguished by the presence of an electro-magnet. Another exhausted bulb, Fig. 218, surrounded by a primary spiral, was contained in a bell-jar, and when the pressure of air in the jar was about that of the atmosphere, the secondary discharge occurred in the bulb, as is ordinarily the case. On exhausting the jar, however, the luminous discharge grew fainter, and a point was reached at which no secondary discharge was visible. Further exhaustion of the jar caused the secondary discharge to appear outside of the bulb. The fact of obtaining no luminous discharge, either in the bulb or jar, the author could only explain on two suppositions, viz.: that under the conditions then existing the specific inductive capacity of the gas was very great, or that a discharge could pass without being luminous. The author had also observed that the conductivity of a vacuum tube without electrodes increased as the pressure diminished, until a certain point was reached, and afterwards diminished again, thus showing that the high resistance of a nearly perfect vacuum is in no way due to the presence of the electrodes. One peculiarity of the discharges was their local nature, the rings of light being much more sharply defined than was to be expected. They were also found to be most easily produced when the chain of molecules in the discharge were all of the same kind. For example, a discharge could be easily sent through a tube many feet long, but the introduction of a small pellet of mercury in the tube stopped the discharge, although the conductivity of the mercury was much greater than that of the vacuum. In some cases he had noticed that a very fine wire placed within a tube, on the side remote from the primary circuit, would prevent a luminous discharge in that tube.

Fig. 219 shows an exhausted secondary coil of one loop containing bulbs; the discharge passed along the inner side of the bulbs, the primary coils being placed within the secondary.

In The Electrical Engineer of August 12, I find some remarks of Prof. J. J. Thomson, which appeared originally in the London Electrician and which have a bearing upon some experiments described by me in your issue of July 1.

I did not, as Prof. J. J. Thomson seems to believe, misunderstand his position in regard to the cause of the phenomena considered, but I thought that in his experiments, as well as in my own, electrostatic effects were of great importance. It did not appear, from the meagre description of his experiments, that all possible precautions had been taken to exclude these effects. I did not doubt that luminosity could be excited in a closed tube when electrostatic action is completely excluded. In fact, at the outset, I myself looked for a purely electrodynamic effect and believed that I had obtained it. But many experiments performed at that time proved to me that the electrostatic effects were generally of far greater importance, and admitted of a more satisfactory explanation of most of the phenomena observed.

In using the term electrostatic I had reference rather to the nature of the action than to a stationary condition, which is the usual acceptance of the term. To express myself more clearly, I will suppose that near a closed exhausted tube be placed a small sphere charged to a very high potential. The sphere would act inductively upon the tube, and by distributing electricity over the same would undoubtedly produce luminosity (if the potential be sufficiently high), until a permanent condition would be reached. Assuming the tube to be perfectly well insulated, there would be only one instantaneous flash during the act of distribution. This would be due to the electrostatic action simply.

But now, suppose the charged sphere to be moved at short intervals with great speed along the exhausted tube. The tube would now be permanently excited, as the moving sphere would cause a constant redistribution of electricity and collisions of the molecules of the rarefied gas. We would still have to deal with an electrostatic effect, and in addition an electrodynamic effect would be observed. But if it were found that, for instance, the effect produced depended more on the specific inductive capacity than on the magnetic permeability of the medium—which would certainly be the case for speeds incomparably lower than that of light—then I believe I would be justified in saying that the effect produced was more of an electrostatic nature. I do not mean to say, however, that any similar condition prevails in the case of the discharge of a Leyden jar through the primary, but I think that such an action would be desirable.

It is in the spirit of the above example that I used the terms "more of an electrostatic nature," and have investigated the influence of bodies of high specific inductive capacity, and observed, for instance, the importance of the quality of glass of which the tube is made. I also endeavored to ascertain the influence of a medium of high permeability by using oxygen. It appeared from rough estimation that an oxygen tube when excited under similar conditions—that is, as far as could be determined—gives more light; but this, of course, may be due to many causes.

Without doubting in the least that, with the care and precautions taken by Prof. J. J. Thomson, the luminosity excited was due solely to electrodynamic action, I would say that in many experiments I have observed curious instances of the ineffectiveness of the screening, and I have also found that the electrification through the air is often of very great importance, and may, in some cases, determine the excitation of the tube.

In his original communication to the Electrician, Prof. J. J. Thomson refers to the fact that the luminosity in a tube near a wire through which a Leyden jar was discharged was noted by Hittorf. I think that the feeble luminous effect referred to has been noted by many experimenters, but in my experiments the effects were much more powerful than those usually noted.

The following is the communication referred to:—

"Mr. Tesla seems to ascribe the effects he observed to electrostatic action, and I have no doubt, from the description he gives of his method of conducting his experiments, that in them electrostatic action plays a very important part. He seems, however, to have misunderstood my position with respect to the cause of these discharges, which is not, as he implies, that luminosity in tubes without electrodes cannot be produced by electrostatic action, but that it can also be produced when this action is excluded. As a matter of fact, it is very much easier to get the luminosity when these electrostatic effects are operative than when they are not. As an illustration of this I may mention that the first experiment I tried with the discharge of a Leyden jar produced luminosity in the tube, but it was not until after six weeks' continuous experimenting that I was able to get a discharge in the exhausted tube which I was satisfied was due to what is ordinarily called electrodynamic action. It is advisable to have a clear idea of what we mean by electrostatic action. If, previous to the discharge of the jar, the primary coil is raised to a high potential, it will induce over the glass of the tube a distribution of electricity. When the potential of the primary suddenly falls, this electrification will redistribute itself, and may pass through the rarefied gas and produce luminosity in doing so. Whilst the discharge of the jar is going on, it is difficult, and, from a theoretical point of view, undesirable, to separate the effect into parts, one of which is called electrostatic, the other electromagnetic; what we can prove is that in this case the discharge is not such as would be produced by electromotive forces derived from a potential function. In my experiments the primary coil was connected to earth, and, as a further precaution, the primary was separated from the discharge tube by a screen of blotting paper, moistened with dilute sulphuric acid, and connected to earth. Wet blotting paper is a sufficiently good conductor to screen off a stationary electrostatic effect, though it is not a good enough one to stop waves of alternating electromotive intensity. When showing the experiments to the Physical Society I could not, of course, keep the tubes covered up, but, unless my memory deceives me, I stated the precautions which had been taken against the electrostatic effect. To correct misapprehension I may state that I did not read a formal paper to the Society, my object being to exhibit a few of the most typical experiments. The account of the experiments in the Electrician was from a reporter's note, and was not written, or even read, by me. I have now almost finished writing out, and hope very shortly to publish, an account of these and a large number of allied experiments, including some analogous to those mentioned by Mr. Tesla on the effect of conductors placed near the discharge tube, which I find, in some cases, to produce a diminution, in others an increase, in the brightness of the discharge, as well as some on the effect of the presence of substances of large specific inductive capacity. These seem to me to admit of a satisfactory explanation, for which, however, I must refer to my paper."

Previous Chapter --- Contents --- Next Chapter

To the Archive Page Discussion on Tesla's Technology

Lab-Tesla disclosures on the technology just presented

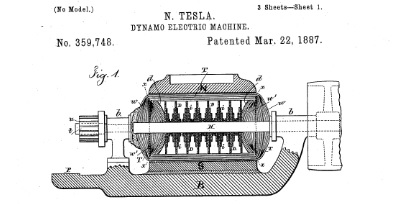

The Lectures of Dr. Nikola Tesla

All lectures are formatted with legible images of the original wood cut block prints

Tesla's Complete Patents

There are 111 unique Tesla Patents

Articles by Tesla

Tesla made public disclosures of means, methods, systems, and apparatus in various articles.

Tesla's Laboratory Power